INCOTERMS, short for International Commercial Terms, are a set of standardized trade terms published by the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) that define the responsibilities and obligations of buyers and sellers in international trade transactions. They specify who is responsible for the costs, risks, and logistics involved in transporting goods from the seller to the buyer.

ISO 14083:2023 is an internationally recognized standard focusing on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions measurement and reporting in freight transport. This standard guides organizations in assessing and managing the environmental impact of their transportation activities.

Import duties, also known as tariffs, are taxes imposed by a country's government on goods brought into the country from abroad. These duties serve several purposes: they generate revenue for the government, protect domestic industries from foreign competition by making imported goods more expensive, and sometimes regulate the volume of imports and exports.

In-gauge cargo is freight that fits within standard dimensions and weight limits, allowing for easier and more cost-effective transportation using conventional shipping methods.

Inbound logistics refers to the process of receiving, handling, and storing raw materials, components, and goods from suppliers to a business or manufacturing facility. This involves the management of various activities, such as transportation, warehousing, inventory control, and material handling.

Inbound supply chain visibility refers to the ability to track and monitor the movement of goods, materials, and shipments as they move from suppliers to a company's receiving or manufacturing facilities.

An inland transport request is a formal request to arrange the movement of goods between a port and an inland destination using land-based transportation methods like trucks or trains.

Intermodal transportation is a logistics strategy that involves using multiple modes of transport, such as trucks, trains, ships, and planes, to move goods from origin to destination. Unlike traditional transportation methods that rely on a single mode of transport, intermodal transportation combines different modes in a coordinated and seamless manner, allowing for greater flexibility, efficiency, and reliability in the supply chain.

The International Convention for Safe Containers (CSC) is a global treaty that sets safety standards for the design, inspection, and maintenance of shipping containers used in international trade.

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations that regulates shipping and maritime safety, promoting secure and environmentally sustainable practices in the global shipping industry.

Inventory turnover refers to the efficiency with which a company manages its inventory by measuring how often inventory is sold and replaced over a specific period. It is an indicator of efficiency and liquidity in inventory management.

LCL (Less than Container Load) freight allows multiple shippers to share space in a single container, making it a cost-effective solution for smaller shipments.

Last mile delivery refers to the final leg of the logistics journey, where goods are transported from a distribution center or fulfillment center to the end destination, typically a residential address or retail store. It is considered the most critical and challenging part of the supply chain due to its complexity and impact on customer satisfaction.

When a shipper submits documentation after a defined deadline set by the carrier.

Laytime is the period of time granted to a vessel for loading and unloading cargo at a port. It represents the duration, typically in a number of days, for which the ship is allowed to remain at the port facility to complete these operations. Laytime is typically agreed upon in charter party contracts between the shipowner or operator and the charterer, who may be the cargo owner or a freight forwarder.

A Lead Logistics Provider (LLP), also known as a Lead Logistics Integrator (LLI), is a supply chain management term referring to a specialized third-party logistics (3PL) provider that takes on a central role in overseeing and coordinating an organization's entire supply chain activities.

Less than truckload (LTL) freight refers to shipments that do not fill an entire truck trailer but instead occupy only a portion of the available space. LTL shipments are typically smaller in size and weight, making them more cost-effective for businesses that do not require full truckload capacity.

In shipping, a letter of indemnity is issued by a shipper or consignee to the carrier, indemnifying them against any potential losses or liabilities arising from the release of cargo without the presentation of required documents, such as bills of lading. This document acts as a legal instrument to facilitate the smooth movement of goods in situations where original documents are unavailable or impractical to obtain.

This is the confirmation sent to the customer, shipper or consignee, that the equipment has been loaded/discharged. This message is based on the "equipment discharge/load report".

The action of lifting any cargo or container on board of the vessel for transportation.

A load board serves as an online platform or marketplace where shippers and carriers can connect to facilitate the transportation of freight. Also known as freight boards or truck load boards, these platforms provide a centralized space for posting and searching available loads and trucks, enabling efficient matching of transportation needs.

List of containers sent by the carrier or its agent to the terminal to instruct which containers must be loaded on a specific vessel/voyage. Each vessel can have several load lists in case of vessel sharing agreements.

Load optimization in logistics refers to the process of efficiently arranging and maximizing the use of available space within transportation vehicles, containers, or storage areas.

In the realm of supply chain and logistics, a load tender refers to the formal request made by a shipper or a consignee to a carrier or transportation provider to transport goods or freight from one location to another. This request initiates the process of arranging transportation services for a specific shipment.

Logistics 4.0, also known as the fourth industrial revolution in logistics, refers to the integration of advanced digital technologies and data-driven solutions to revolutionize traditional supply chain and logistics operations. It builds upon the concepts of Industry 4.0, applying automation, artificial intelligence (AI), Internet of Things (IoT), and big data analytics to optimize efficiency, visibility, and agility across the supply chain.

Logistics document management refers to the process of handling, organizing, and storing various documents involved in supply chain and logistics operations. It encompasses the management of paperwork, electronic records, and other documentation essential for the efficient flow of goods from point of origin to final destination.

Logistics route optimization involves the strategic process of determining the most efficient and cost-effective routes for transporting goods and materials from origin to destination. It aims to minimize transportation costs, reduce fuel consumption, and enhance overall delivery efficiency within supply chain and logistics operations.

A Logistics Service Provider (LSP) is a company or organization that offers specialized logistics and supply chain management services to support the transportation, storage, and distribution of goods. LSPs play a crucial role in facilitating efficient movement of products from point of origin to point of consumption, serving as intermediaries between manufacturers, suppliers, and end-users.

Logistics visibility refers to the ability of supply chain professionals to track and monitor the movement of goods and assets throughout the supply chain in real-time. It involves gaining insights into the location, status, and condition of shipments, inventory, and transportation assets as they move through various stages of the supply chain.

The manifest corrector is used to make changes to a manifest after the manifest in question has been submitted to the relevant authorities.

Marine insurance offers protection for shipments and vessels involved in maritime trade. It covers various risks, including damage to cargo caused by accidents, theft, natural disasters, and even piracy. Additionally, marine insurance can provide coverage for liabilities arising from collisions, salvage operations, and pollution incidents during transportation by sea.

A Maritime Mobile Service Identity (MMSI) number is a unique nine-digit identifier assigned to ships, coastal stations, and other maritime communication equipment. This number is used in digital selective calling (DSC), automatic identification systems (AIS), and other marine radio communication systems to ensure accurate and efficient identification and communication.

A Master Bill of Lading (MBL) is a transportation document issued by the ocean carrier or its agent to acknowledge receipt of goods for shipment. It serves as a contract of carriage between the shipper and the ocean carrier, detailing the terms and conditions of transportation, including the type, quantity, and destination of the goods being shipped. The MBL also acts as a receipt for the cargo and serves as a title document, allowing the consignee to claim ownership of the goods upon arrival at the destination port.

Material Requirements Planning (MRP) is a systematic approach to managing the manufacturing and procurement of materials necessary for production. It involves calculating the quantities of raw materials, components, and assemblies needed to fulfill production orders or meet demand forecasts within a specified timeframe.

Merchant haulage refers to a scenario in transportation logistics where the party responsible for arranging and paying for the inland transportation of goods (e.g. port to warehouse) is the cargo owner or another party distinct from the ocean carrier.

MOQ, or Minimum Order Quantity, refers to the smallest quantity of goods or products that a supplier is willing to sell or a buyer is willing to purchase in a single order. It is a contractual agreement between the supplier and the buyer, setting a threshold below which the transaction may not be economically feasible for one or both parties.

Multimodal transport refers to the transportation of goods using two or more modes of transport under a single contract. It integrates different types of transportation modes, such as road, rail, sea, and air, to optimize the efficiency of cargo movement from origin to destination.

Neopanamax ships are large cargo vessels designed to navigate the expanded Panama Canal, offering increased cargo capacity and efficiency compared to earlier Panamax vessels.

The operational capacity of a vessel on a specific voyage. This capacity takes into account all limiting factors such as the physical capacity on-board, but it also allows for constraints in the terminals to load / discharge the vessel for the specific voyage.

NVOCC stands for Non-Vessel Operating Common Carrier and refers to a type of freight consolidator or intermediary that doesn't own any vessels but functions as a carrier by issuing bills of lading, booking space on vessels, and managing shipments. Essentially, NVOCCs act as intermediaries between shippers and ocean carriers, providing shipping services without operating their own vessels.

Off dock storage refers to the practice of storing cargo containers or goods at a location separate from the port terminal or container yard where they were initially unloaded from a vessel. This storage facility, often located nearby but off-terminal, provides additional space for holding containers temporarily before they are moved to their final destination.

OTIF stands for On-Time In-Full, a key performance indicator (KPI) used in supply chain management to measure the percentage of orders delivered to customers both on time and in full. It assesses the effectiveness and efficiency of logistics operations in meeting customer expectations regarding delivery timeliness and order completeness.

Order accuracy in logistics and warehousing refers to the precision with which customer orders are fulfilled.

Order lead time, often referred to simply as lead time, is a crucial concept in supply chain management that defines the duration between the initiation of an order and its fulfillment. It encompasses the entire process from when an order is placed until the goods or services are delivered to the customer or stocked in inventory.

Out of gauge cargo, often abbreviated as OOG cargo, refers to shipments that exceed the standard dimensions or weight limitations for transportation containers or transport vehicles. This type of cargo typically includes oversized, bulky, or irregularly shaped goods that cannot fit within the standard confines of a shipping container or vehicle.

A Pre-Arrival Processing System (PAPS) number is a tracking number used in the United States for road shipments that require pre-arrival customs processing. PAPS is a border-crossing process designed to expedite the clearance of goods entering the U.S. by allowing customs to review shipment information before it reaches the border.

A Pre-Arrival Review System (PARS) number is a unique identifier used in the Canadian border clearance process for road shipments entering Canada. The PARS number allows the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) to review shipment information before the goods arrive at the border, facilitating faster and more efficient customs clearance.

POD (Port of Discharge) refers to the specific port where goods are unloaded from a vessel at the end of their sea voyage. This term is integral in the logistics and supply chain industry as it marks the point where cargo is transferred from the shipping carrier to the next mode of transportation, such as trucks or trains, or directly to the consignee.

POL (Port of Loading) refers to the specific port where goods are loaded onto a vessel for transportation. In international shipping, the POL is a critical point in the logistics process, marking the beginning of the goods' journey from the exporter to the importer.

A packing list is a document that itemizes the contents of a shipment. It provides detailed information about the goods being transported, including descriptions, quantities, and any special instructions for handling. This document serves as a crucial tool in supply chain and logistics operations, aiding in the verification of goods received, inventory management, and customs clearance processes.

A Panamax ship is a vessel designed to meet the size restrictions of the original Panama Canal locks.

A facility with piers or docks. Ports are accessed by vessels and represent the destinations of a voyage. Ports can contain one or more terminals.

A port call is a scheduled stop made by a vessel at a port for loading, unloading, and other operational activities related to shipping. A vessel may have several terminal calls during a single port call.

Port congestion occurs when there is a significant backlog of vessels waiting to enter or leave a port, or when there are delays in cargo loading and unloading processes within the port. It results in extended wait times for ships, increased dwell times for cargo, and overall disruptions to supply chain operations.

A port of entry refers to a designated location where goods and merchandise can legally enter a country for customs inspection and clearance. It serves as the gateway through which imported goods are received and undergo official procedures before being allowed into the domestic market.

Port pair is a term used in the shipping and logistics industry to describe a set of two ports that serve as the origin and destination in a shipping route. A port pair consists of a Port of Loading (POL) and a Port of Discharge (POD).

A Post Panamax vessel is a large ship too big for the original Panama Canal locks but smaller than newer Neopanamax vessels.

Re-export refers to the process of exporting goods that were previously imported into a country without undergoing significant alteration or manufacturing processes within that country. Essentially, re-exports involve sending imported goods back out of the country to a different destination.

Real time transportation visibility refers to the ability of supply chain professionals to monitor and track the movement of goods and shipments in real time throughout the transportation process. It involves gaining insights into the location and status of shipments as they move through various modes of transportation, such as road, rail, air, or sea.

A reefer container, also known as a refrigerated shipping container, is a specialized shipping container used to transport temperature-sensitive cargo such as fruits, vegetables, pharmaceuticals, and other perishable goods. These containers are equipped with refrigeration units to maintain specific temperature conditions throughout the journey, ensuring the freshness and quality of the cargo.

Reference number contained in the Cargo Release. It is provided by the carrier to the terminal and to the cargo receiver, and it must be presented upon pick up at the terminal.

Reverse logistics refers to the process of managing the flow of products, materials, and information from the point of consumption back to the point of origin or other designated locations. It involves activities such as product returns, repairs, refurbishment, recycling, and disposal, aimed at optimizing the value recovery and sustainability of goods throughout their lifecycle.

Roll-on/roll-off (RORO) shipping is a method of transporting vehicles and other wheeled cargo by allowing them to be driven onto and off of specialized vessels, eliminating the need for cranes or other loading equipment. RORO vessels are equipped with ramps or platforms that facilitate the easy movement of cargo.

Plan for the end-to-end shipment of a shipment. This includes specification of all transport legs, timings, schedules and interdependencies between transport legs.

SCAC stands for Standard Carrier Alpha Code. It's a unique two-to-four letter code assigned to transportation companies for easy identification in the supply chain. These codes are primarily used in the United States, Canada, and Mexico.

Safety stock, also known as buffer stock or reserve inventory, refers to the extra inventory held by a company above its average demand level. The purpose of safety stock is to provide a buffer against unexpected fluctuations in demand, supply disruptions, or lead time variability.

Sanctions screening is the process of verifying that individuals, companies, and entities involved in a business transaction are not subject to any trade or economic sanctions imposed by governments or international organizations. This process is essential to ensure compliance with legal and regulatory requirements and to avoid engaging in prohibited activities.

Scope 3 emissions refer to indirect greenhouse gas emissions generated by activities associated with an organization's value chain, including its upstream and downstream activities such as procurement, transportation, product use, and disposal. These emissions occur outside of an organization's direct control but are a result of its business activities.

A sea waybill, also known as a non-negotiable sea waybill or direct ocean carrier bill of lading, is a document issued by the carrier to acknowledge receipt of goods and confirm the contract of carriage. Unlike a traditional bill of lading, a sea waybill is not a negotiable instrument and does not require endorsement for the transfer of ownership. It serves as a receipt of shipment and a contract of carriage between the shipper and the carrier.

A single-use instrument used for securing container or freight car or truck doors.Seals have unique numbers for record purposes.

A Shipment is the realisation of a customer booking for which all containers have a common routing and details of scheduling.

Shipment visibility refers to the ability of supply chain and logistics professionals to track and monitor the movement of goods throughout the entire logistics process, from the point of origin to the final destination. It involves real-time access to information about the status and location of goods as they travel through various stages of transportation and distribution.

The shipper is the entity or party who is responsible for the shipment. This can be dependent on the INCOTERMS under which the cargo moves. If there are any queries around this, please contact your Beacon Account Manager.

A shipping alliance is a collaboration between multiple shipping companies to share resources and optimize operations, enhancing service offerings and reducing costs in the global shipping market.

An enrichment to the original booking shared by the shipper to the carrier. The shipping instruction includes volume/weight, shipping dates, origin, destination and other special instructions. The information given by the shipper through the shipping instructions is the information, which is required to create the Bill of Lading.

Shipping lanes are predetermined routes used by ships and vessels for transporting goods and commodities across oceans and seas. These routes are established to ensure safe and efficient maritime navigation, taking into account factors such as water depth, currents, weather conditions, and proximity to ports.

A shipping manifest is an essential document in the logistics process, detailing all items being transported on a ship, airplane, or vehicle. It includes information such as the names and addresses of the shipper and consignee, descriptions of the cargo, the quantity and weight of each item, and any special handling instructions. The manifest helps ensure that all parties involved in the shipping process, including customs authorities and logistics providers, have a clear understanding of the cargo being transported.

A short shipment refers to a situation in logistics where the quantity of goods received by the consignee is less than what was originally shipped or expected. It can occur due to various reasons such as inventory discrepancies, packaging errors, transportation issues, or supplier mistakes. Short shipments can disrupt supply chain operations, delay production schedules, and impact customer satisfaction.

Slotting refers to the strategic placement of products within a warehouse to optimize the efficiency of picking, packing, and shipping processes. This involves organizing products based on factors such as their size, weight, demand frequency, and compatibility with other items.

Joint term for cargo, which is not transported in a regular dry container or is considered dangerous goods. This also includes, but is not limited to out of gauge cargo.

All container types other than regular Dry or Reefer containers. Examples of these can be flat racks (open containers for oversized, irregular and/or heavy cargo), Open tops (fitted with a solid removable roof), etc.

A stockout occurs when a business runs out of a particular item or product, leading to its temporary unavailability for sale or distribution. It denotes a situation where customer demand exceeds available inventory, resulting in potential lost sales and customer dissatisfaction.

Stowage refers to the systematic loading and arrangement of cargo on a vessel to ensure safety, efficiency, and optimal use of space during transportation.

Supplier risk management is the process of identifying, assessing, and mitigating risks associated with a company's suppliers to ensure continuity and reliability in the supply chain.

Supply Chain 3.0 represents the evolution of traditional supply chain management practices into a more advanced and interconnected model, driven by digital technology and data analytics. This next-generation supply chain approach focuses on enhancing visibility, agility, and collaboration across the entire supply chain ecosystem.

Supply Chain 4.0, an integral part of the broader concept of Industry 4.0 and Logistics 4.0, represents a paradigm shift in supply chain management driven by digital technologies and advanced analytics. It encompasses the integration of artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning, robotics, and the Internet of Things (IoT) to create smarter, more connected, and automated supply chain networks.

Supply chain automation involves the use of technology and software systems to streamline and optimize various processes within the supply chain, including inventory management, order fulfillment, transportation, and warehouse operations. It aims to reduce manual intervention, improve efficiency, and enhance overall supply chain performance.

Supply chain collaboration refers to the strategic partnership and cooperation among different entities within the supply chain, including suppliers, manufacturers, distributors, warehouses and retailers. It involves sharing information, resources, and responsibilities to optimize processes, improve efficiency, and achieve common goals.

A supply chain control tower is a centralized hub or platform that provides end-to-end visibility and orchestration of supply chain operations in real-time. It acts as a command center where supply chain professionals can monitor, analyze, and manage the flow of goods, information, and finances across the entire supply chain network.

Supply chain data refers to the information generated and collected throughout the entire supply chain process, from procurement of raw materials to delivery of finished products to customers. It encompasses various types of data, including inventory levels, transportation routes, freight tracking milestones, supplier performance, demand forecasts, and customer preferences. Supply chain professionals can analyze this data to gain insights, optimize processes, and make informed decisions to improve efficiency and planning.

Supply chain finance (SCF) refers to a set of financial solutions and practices aimed at optimizing cash flow and working capital management throughout the supply chain. It involves leveraging financial instruments and services to facilitate transactions between buyers, suppliers, and financial institutions, thereby improving liquidity, reducing risk, and enhancing collaboration within the supply chain.

Network design in supply chain management involves creating a strategic framework that outlines the structure and operations of the supply chain.

Supply chain resilience refers to the ability of a supply chain to withstand and recover from disruptions while maintaining continuous operations and delivering products or services to customers without significant impact. It involves the capacity to anticipate, adapt, and respond effectively to various challenges, including natural disasters, geopolitical events, market fluctuations, and supplier disruptions.

Supply chain risk management refers to the process of identifying, assessing, and mitigating risks within a supply chain to ensure continuity and minimize disruptions. It involves analyzing all elements of the supply chain—from sourcing raw materials to delivering finished products—to anticipate and address potential vulnerabilities that could impact operations, finances, or reputation.

Supply chain traceability refers to the ability to track and verify the journey of products through every stage of the supply chain, from raw materials to the final consumer.

Also referred to as end-to-end visibility, supply chain visibility refers to the ability of organizations to track, analyze, communicate and monitor the flow of goods as they move across the entire supply chain, from raw material suppliers to end customers. It encompasses real-time data and insights into inventory levels, order statuses, transportation movements, and other key metrics, enabling stakeholders to make informed decisions and respond swiftly to changes and disruptions.

Supply planning is the process of aligning supply with demand to ensure that sufficient quantities of goods or materials are available to meet customer needs while minimizing costs and optimizing inventory levels. It involves forecasting demand, determining production or procurement requirements, scheduling production activities, and managing inventory levels to maintain a balance between supply and demand.

A facility for loading, moving or discharging containers. Terminals can be both inland terminals for trucks and rail or port terminals are accessed by vessels and these can contain multiple berths.

Upon completion of operations on a particular vessel, a terminal departure report (TDR) is to be sent to the respective shipping lines. This report, prepared from timesheets, includes container vessel operation data and tabulation of productivity. This can be in the form of the EDI-message TPFREP.

Each terminal has a set number of moves, which can be performed on a vessel during a port call. One move is usually defined as the movement (loading or unloading) of one container.

The power of sustainable supply chains: Everything you need to know to take action and lead the way

None of us work alone. We’re all part of global supply chains that stretch from Shanghai to Sheffield and from Sydney to San Francisco. And that’s why it’s so important for everyone involved in manufacturing, shipping, and distribution to play their part in making their segment of those supply chains as sustainable and environmentally responsible as possible.

It’s no small task though. Even the most switched-on and visibly sustainable companies out there have plenty of work to do – because cleaning up direct carbon emissions is just a drop in the ocean compared to tackling the indirect emissions from your supply chain.

In fact, a large-scale McKinsey study in 2016 found that “the typical consumer company’s supply chain creates far greater social and environmental costs than its own operations, accounting for more than 80 percent of greenhouse-gas emissions and more than 90 percent of the impact on air, land, water, biodiversity, and geological resources.”

So although many companies have switched to renewable energy and other sustainable ways of operating within their premises, the overall effects of their operations may not have changed very much at all.

Luckily, it’s not all doom and gloom. Companies are taking responsibility for their supply chains. Cleaning them up and making systematic changes to keep them that way.

New sustainable supply chain management technology is helping by making it easier to track, report and reduce your carbon footprint. There’s never been a better time to make the adjustments that will change our world for the better.

Sustainable supply chains are no longer optional

While we all like to think companies do the right things for the right reasons, there are still costs associated with driving sustainability in supply chains. In the past, that might have meant it would fall down a company’s list of priorities – and that’s totally understandable. Deciding between an investment in sustainability and something else like opening a new factory or expanding into a different region is never an easy choice.

A few years ago, a lot of companies may have gravitated towards the latter options. But that’s changing. Ernst & Young’s 2022 survey of supply chain leaders reveals that “visibility throughout the supply chain is the top priority for supply chain executives”, up from second place in the two years before.

This is partly because there are cost-saving and revenue growth benefits to more efficient supply chain management. But another common theme from the survey is that supply chain visibility is becoming a much greater priority as businesses face added pressure from customers, employees, and government regulators. Particularly when it comes to carbon emissions, sustainable sourcing, and labor conditions.

Who is demanding more sustainable supply chains?

In the court of public opinion, sustainability has never mattered more. If a company isn’t seen to be taking appropriate steps, there’s a real risk that its customers might take their business to a more responsible partner.

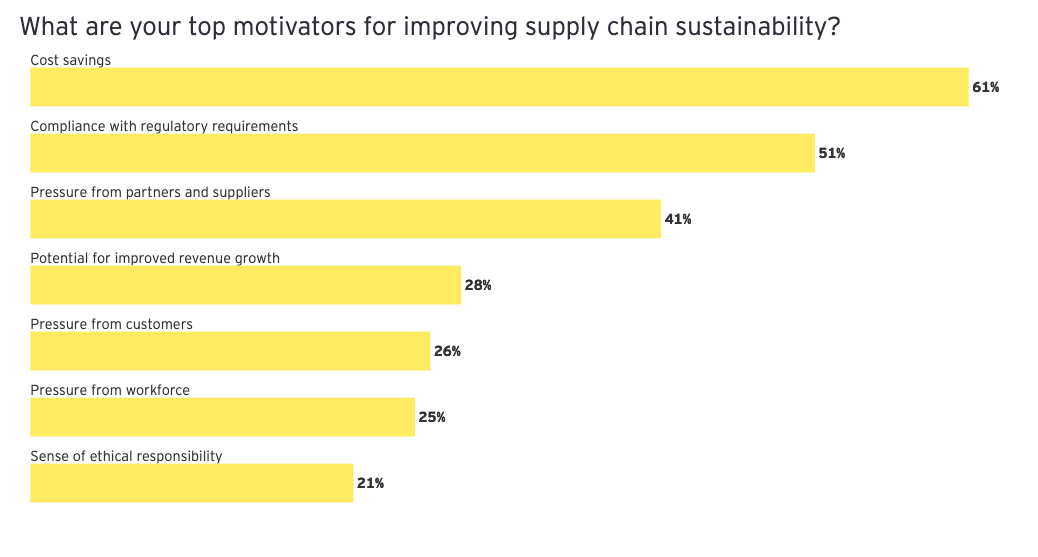

That same Ernst & Young survey shows that pressure from customers is the fifth-strongest motivator for improving supply chain sustainability, with higher expectations from employees sitting just behind it.

Input from partners and suppliers also plays a part. But aside from the potential savings that are always going to be the biggest driver of change, the dominant influencing factor is new regulations that are forcing the hands of even the most resistant companies.

For example, the EU is in the process of introducing new sustainability standards that require companies to audit their full global supply chains including every single one of their direct and indirect relationships. The goal of this is to make sure organizations in the EU are fully compliant with not only environmental protocols, but human rights and governance standards too.

Similar regulations are either in place, in progress, or being discussed all over the world. It’s only a matter of time before they become the norm, so the conversation is now a matter of ‘when’, not ‘if’, the evolution happens.

Plus, the more companies that prioritize sustainability in supply chains, the easier it becomes for others to follow in their footsteps – taking advantage of the new tech and ways of working that the leaders are pioneering.

That’s the knock-on effect at play. Once enough of us decide to make a change, the people we work with will be empowered and incentivized to do the same.

To get there though, we all need a thorough understanding of what sustainable supply chains are, and the tools that can be leveraged make them a reality.

What is supply chain sustainability?

You might think sustainability is solely about the environment. That’s obviously a huge part of it, but for anything to be truly sustainable, there’s a lot more that has to happen at every step along the way.

In supply chains, sustainability is broken down into three core focus areas: environmental, social, and governance.

This is ESG, and nothing new to most of us. But it’s worth recapping how those three pieces of the puzzle work together in relation to a supply chain.

Environmental supply chain sustainability

It’s impossible to underplay the environmental importance of sustainability in supply chains. That’s because the consequences are some of the most severe – ranging from toxic waste leaks and water pollution to deforestation and long-term damage to the ecosystems our planet relies on to thrive.

To avoid these, there are a lot of different pieces of the supply chain to consider. It’s not just about reducing emissions – although that’s vital.

You’ll need to think about the materials used along the way (like plastic or anything else that’s potentially hazardous to the environment). You’ll also need to work out whether your supply chain is wasting or polluting water – and even if it’s contributing to a loss of biodiversity indirectly through deforestation.

That’s a lot to keep track of, which is why better supply chain visibility is vital. The more you can see and measure, the more you can change and improve. With the right data at your fingertips, you can start benchmarking performance and looking for ways to make a difference.

Social supply chain sustainability

Supply chains are about people too. If every single piece of the process is working in an environmentally friendly way, that’s not worth very much if workers’ health, safety, or human rights are being compromised.

That’s what the ‘S’ in ESG stands for – social. And it means taking ownership of the effects our supply chains have on the lives of everyone involved with or affected by them.

Some of these responsibilities are obvious, like maintaining the very best labor and human rights standards, along with appropriate health and safety measures. But others are slightly more complicated, like ensuring everybody in your supply chain is getting fair pay, and working in environments that support diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Responsible partners will care just as much about these things as you do. So when you start having conversations with suppliers about the importance of sustainability in your shared supply chains, make sure how people are treated is front and center.

Governance supply chain sustainability

Governance is an umbrella term for the way that organizations are managed and run. In supply chains, it refers to all the different rules, regulations, systems, and structures to follow as best practices.

That means having proper risk management tools in place to protect your partners, avoid corruption and bribery, and stick to whatever codes of conduct your organization is obligated to follow. It also means prioritizing transparency, and regularly reporting on different areas of your operations so that partners and customers can see the proof behind your claims about sustainability.

These are all things that you should be expecting your partners to do. If you’re not sure whether they’re following the rules, then it might be time to have a conversation or start rethinking those relationships.

When ESG is a priority, sustainability follows

For a supply chain to be truly sustainable, every person and company involved has to be doing their bit at an environmental, social, and governance level. It can be a lot to manage. But when it happens, supply chains do a lot better for people and the planet.

Even though there are all sorts of factors involved, a lot of them are intertwined and interrelated. A company following a clear code of conduct and managing risk sustainably is going to naturally treat employees better and look for ways to reduce its environmental impact. Just like how making sure a manufacturing process isn’t polluting waterways will have a positive effect on the data you collect – incentivizing greater transparency in reporting.

Little by little, ESG flows through the full supply chain, ultimately making every stage more cost-effective and more sustainable.

Best practices for supply chain sustainability – step by step

Because the ESG elements of supply chains are so interwoven, it doesn’t always make sense to use them as a starting point for your sustainability plan. Instead, it’s often easier to simply break the full supply chain down into different chunks, and then target those specific areas.

So let’s take a look at the key segments of a supply chain and how you can drive sustainability in each of them.

Procurement and purchasing

Before any supply chain can start moving, you’ll need something to move. That’s the procurement stage, when you’ll source the products, materials, or services you need to get things up and running.

Traditionally, companies with a focus on sustainability in supply chains might have focused less on procurement and more on transportation or warehousing. But a recent survey from the Institute for Supply Management shows a growing emphasis on this first step, with leaders from all sectors realizing that better purchasing practices can “create a long-term competitive advantage for their company."

So what does that look like? Well, it all starts with better, more responsible resourcing and stringent vetting before deciding to work with a particular partner. That might include audits, checking qualifications and certifications, or providing incentives that relate to sustainability performance.

But this isn’t just about onboarding new partners. Sustainable companies should also take stock of their existing procurement network, and apply all the same strategies to make sure a long-term partner isn’t compromising your overall supply chain.

Transportation and shipping

We all know that transportation is the foundation of a supply chain.

It’s also one of the most challenging areas of sustainability to address, with air, sea and land transportation making up 15% of greenhouse gas emissions globally.

This is a major focus area at the international regulatory level, so it’s no surprise that almost all supply chain transport providers are investigating and investing in alternate ways of doing things. Those range from investing in alternative fuels all the way through to more energy-efficient ship designs, and the knock-on benefits can be a real boost to your supply chain sustainability.

That gives you options, making it easier to pick and choose providers who are prioritizing sustainability – but only if you’ve got the right information to make those decisions with.

Beacon’s carbon tracking tools are a great place to start, empowering cleaner, greener shipping by making it easy for you to see the full picture of any emissions associated with your shipping.

Once you’ve got that, the ways you reduce your impact are up to you. More strategic route and partner planning is one option, choosing transport companies that use renewable energy or take various steps to limit pollutants. But you can also look at balancing your emissions with carbon offsetting for true net zero. Beacon lets you do that too, thanks to industry-leading offsetting tools powered by our partnership with Lune.

Storage and warehousing

No matter what your supply chain is moving, you’ll need somewhere to keep it. Storage is one of the areas of the supply chain that you might have more control over if it happens on premises that you manage directly. And that makes it a clear opportunity for improved sustainability.

Investing in warehouse fit-outs that reduce their carbon footprints should be your first step. BREEAM’s third-party certified standards are the benchmark for sustainable built environments, and using those standards as a guide can help you reduce your carbon footprint and increase operational efficiency – meaning you’ll save money on running costs too. The standards cover everything from water and energy use to pollutants and waste disposal, so work your way through the list and make sure your facilities are reaching as high a level as possible.

You can also invest in non-building factors like electric fleets and multi-use forklifts, which lower your carbon footprint further. Alternatively, optimized warehouse storage systems make it possible to reduce inventory and minimize the amount of product that’s shifted around unnecessarily.

Ensuring the right health and safety measures are in place is just as important as the environmental side of things, to make sure your sustainability efforts are improving and protecting the lives of team members as well as the world around them.

Of course, a lot of us store goods and products off-site, but all the same steps apply. You’ll just need to spend a bit more time in discussions with your warehousing partner to make sure they’re pulling out all the same stops that you would in their position.

Technology

While technology isn’t an area that necessarily hurts sustainability, it can create enormous potential for positive change.

More and more companies are making the move to renewable energy in their warehouses, plants, and offices – installing solar panels that reduce their carbon impact and limit reliance on fluctuating energy prices.

The benefits of technology are also visible in new types of supply chain sustainability software, which work to make every part of the process more visible, and therefore easier to optimize for ESG. But the benefits don’t stop there. New tech like Beacon is also disrupting the ways that companies track, plan, and report – empowering people at every stage of the supply chain with richer data and the insights they need to improve.

Packaging

Sustainability is nothing new in packaging. These days, we’re all familiar with recyclable materials and circular manufacturing processes that produce less waste and make what we produce easier to get rid of safely.

But there’s always room to do more. With increased levels of online shopping driving more paper, cardboard, and plastic packaging than ever, it’s an area of the supply chain that can always be improved.

Cutting out as much plastic as possible helps, as it is more pollutive and harder to recycle than other alternatives. But you can go a step beyond by exploring fully recycled packaging, or introducing plant-based materials made from natural, biodegradable sources like sugarcane or cornstarch.

From carbon-neutral cartons to sachets made of seaweed, those products are out there, and making the switch is a simple way to instantly and significantly cut down waste.

You may also want to run a packaging audit and rethink your designs entirely – looking for ways to do more with less by reducing weight and size, or eliminating unnecessary elements or purely cosmetic layers. The trade-off you get in looks is easily outweighed by the positive benefits you’ll be able to shout about to your customers and partners.

Reverse logistics

Supply chains usually focus on getting something, somewhere. But what about getting it back? Reverse logistics are a bigger part of our industry than ever, with higher volumes of online shopping naturally leading to knock-on higher returns levels.

What you do with those returns can have a critical impact on sustainability. So look for ways to innovate by repurposing and recycling returned or faulty goods – or by refurbishing and reselling.

You can go further by offering to take back products that have already been used and turn them into something new. That’s already happening in certain sectors like clothing, and it’s a great way for forward-thinking companies to gain an edge both on future production costs and in the minds of their customers.

If any of your materials are perishable, look for ways to shift expiring product earlier, or to safely dispose of it on-site rather than sending it to landfill. There may be up-front costs linked to introducing these sorts of processes, but over time the savings will add up. Plus, you’ll be able to rest easy knowing you’re already a few steps ahead of whatever regulations around waste may come in the future.

How else can you make your supply chain more sustainable?

Even if you’re following all the best practices for supply chain sustainability, there are still plenty of other ways to keep yourself ahead on the road to responsibility.

Set clear, realistic objectives and measure your progress

You won’t be able to make a lasting change if you don’t have the historical information and regular benchmarking to see where you’re making progress. That’s where data comes in, giving you a clear, up-to-date picture of your overall supply chain sustainability and any areas within it where there’s still work to do.

Your first step should always be a thorough audit of your full supply chain using dedicated sustainable supply chain management tools like Beacon, which you can then build into specific targets and goals. Those might be based on what your competitors are doing, or you may want to sign up for a certain target through a program like the Science Based Targets initiative.

Whatever goal makes the most sense, once you’ve got it, you’ll need to make sure you know how close you are to achieving it. That’s another area where software helps, giving you real-time insight into how your adjustments are adding up to real change.

Engage and communicate with partners and customers

Last but not least, lasting sustainability means taking all of the information you have and the progress you’ve made and making it accessible to others. That could be through direct conversations, or publishing regular, transparent reports that show your journey from A to B – and the steps you took to get there.

Some of your supply chain partners might not be as aware of the ways they can improve their performance. But by sharing your expertise, you can help them implement similar checks and balances into their own operations.

That’s nothing but good news for you as part of their supply chains, because the benefits really do flow both ways – giving everyone in your supply chain sustainability performance to be proud of.

Plus, transparency is something your end-customers will value just as much as your partners. Nobody wants to be accused of greenwashing – talking the talk about sustainability without backing it up with tangible change.

But if you can show that you’re making a concerted effort to do better at environmental, social, and governance levels, your customers will know that continuing to choose you is a responsible option for the long term.

Make sustainability a priority and lead the way in your supply chain

There are hundreds of different ways to prioritize sustainability. But it’s only by embedding it into your organization from the top down that you’ll be able to take all the steps needed to become a leader rather than a follower.

That’s what’ll keep you ahead of the regulations that are only going to become stricter as time goes on, while helping you stand out and stand prouder in a market where morals matter more than ever.

There’s no better time than right now to put a plan in place that makes your supply chain a more sustainable one.

Following all the steps in this guide will give you the right foundations, and investing in cutting-edge technology means you’ll be ready to build on them. So start measuring your carbon footprint today and making your supply chain more sustainable for tomorrow.

.png)